When their poverty is urged as an argument against their religion and social system they assert that the true follower of the prophet will be poor and suffer much in this world but that his condition in the "new world above the sky" will be in direct contrast. They therefore esteem poverty, lowly surroundings and sickness as a sure indication of a rich heavenly reward and point to the better material surroundings and wealth of their brethren of the white man's way as an evidence that the devil has bought them.

The writer of this sketch has no complaint against the simple folk who have long been his friends. For a greater portion of his lifetime he has mingled with them, lived in their homes and received many honors from them. He has attended their ceremonies, heard their instructors and learned much of the old-time lore. Never has he been more royally entertained than by them, never was hospitality so genuine, never was gratitude more earnest, never were friends more sincere. There is virtue in their hearts and a sincerity and frankness that is refreshing. If only there were no engulfing "new way" and no modern rush, no need for progress, there could scarcely be a better devised system than theirs. It was almost perfectly fitted for the conditions which it was designed to meet, but now the new way has surrounded them, everything which they have and use in the line of material things, save a few simple maize foods and their ceremonial paraphernalia, is the product of the white man's hand and brain. The social and economic and moral order all about them is the white man's, not theirs. How long can they oppose their way to the overwhelming forces of the modern world and exist? How long will they seek to meet these overwhelming forces with those their ancestors devised but devised not with a knowledge of what the future would require? My Indian friends will answer, "Of these things we know nothing; we know only that the Great Ruler will care for us as long as we are faithful." Asked about the clothes they wear, the houses they live in, the long house they worship in, they reply, "All these things may be made of the white man's material but they are outside things. Our religion is not one of paint or feathers; it is a thing of the heart." That is the answer; it is a thing of the heart--who can change it?

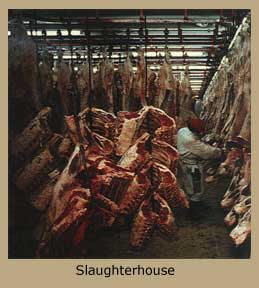

And, we do so, violently. Do we consider the Earth a sentient being? Consider, then, the violent act of mining--drilling deeply and forcefully into the body of the earth. Consider, also, the violence when the endless mine shafts collapse, taking the lives of countless workers and devastating family members left behind. Woodlands are demolished in service of providing fortunes for developers who pack countless homes into tidy parcels of land to profit from consumers. Do we think about the bulldozed trees that, for decades, and sometimes for centuries, cleaned our air and maintained our soil, providing habitat for the many birds and squirrels. Do we consider the impact on the animal life disturbed as a result of this so-called progress? Countless animals are killed in the slaughterhouses. Do we think to thank them for the sacrificing of their lives for our sustenance at our table?

And, we do so, violently. Do we consider the Earth a sentient being? Consider, then, the violent act of mining--drilling deeply and forcefully into the body of the earth. Consider, also, the violence when the endless mine shafts collapse, taking the lives of countless workers and devastating family members left behind. Woodlands are demolished in service of providing fortunes for developers who pack countless homes into tidy parcels of land to profit from consumers. Do we think about the bulldozed trees that, for decades, and sometimes for centuries, cleaned our air and maintained our soil, providing habitat for the many birds and squirrels. Do we consider the impact on the animal life disturbed as a result of this so-called progress? Countless animals are killed in the slaughterhouses. Do we think to thank them for the sacrificing of their lives for our sustenance at our table?

It goes up to God. When we offer it, we are telling our God that we are speaking the truth. Wherever there’s tobacco offered, everything is wakan - sacred, or filled with power. We make a promise to speak the truth. That’s why we Indians got into trouble with the white man’s ways early on. When we make a promise, it’s a promise to the Great Spirit, Wakan Tanka. Nothing is going to change that promise. We made all these promises with the white man, and we thought the white man was making promises to us. But he wasn’t-he was making deals. We could never figure out how the white man could break every promise, especially when all the priests and holy men were involved. We can’t break promises.

It goes up to God. When we offer it, we are telling our God that we are speaking the truth. Wherever there’s tobacco offered, everything is wakan - sacred, or filled with power. We make a promise to speak the truth. That’s why we Indians got into trouble with the white man’s ways early on. When we make a promise, it’s a promise to the Great Spirit, Wakan Tanka. Nothing is going to change that promise. We made all these promises with the white man, and we thought the white man was making promises to us. But he wasn’t-he was making deals. We could never figure out how the white man could break every promise, especially when all the priests and holy men were involved. We can’t break promises.